Exploring the Security Risks of AI Assistants like OpenClaw

February 3, 2026

min read

Introduction

OpenClaw (formerly Moltbot and ClawdBot) is a viral, open-source autonomous AI assistant designed to execute complex digital tasks, such as managing calendars, automating web browsing, and running system commands, directly from a user's local hardware. Released in late 2025 by developer Peter Steinberger, it rapidly gained over 100,000 GitHub stars, becoming one of the fastest-growing open-source projects in history. While it offers powerful "24/7 personal assistant" capabilities through integrations with platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, it has faced significant scrutiny for security vulnerabilities, including exposed user dashboards and a susceptibility to prompt injection attacks that can lead to arbitrary code execution, credential theft and data exfiltration, account hijacking, persistent backdoors via local memory, and system sabotage.

In this blog, we’ll walk through an example attack using an indirect prompt injection embedded in a web page, which causes OpenClaw to install an attacker-controlled set of instructions in its HEARTBEAT.md file, causing the OpenClaw agent to silently wait for instructions from the attacker’s command and control server.

Then we’ll discuss the architectural issues we’ve identified that led to OpenClaw’s security breakdown, and how some of those issues might be addressed in OpenClaw or other agentic systems.

Finally, we’ll briefly explore the ecosystem surrounding OpenClaw and the security implications of the agent social networking experiments that have captured the attention of so many.

Command and Control Server

OpenClaw’s current design exposes several security weaknesses that could be exploited by attackers. To demonstrate the impact of these weaknesses, we constructed the following attack scenario, which highlights how a malicious actor can exploit them in combination to achieve persistent influence and system-wide impact.

The numerous tool integrations provided by OpenClaw - such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Discord - significantly expand its attack surface and provide attackers with additional methods to inject indirect prompt injections into the model's context. For simplicity, our attack uses an indirect prompt injection embedded in a malicious webpage.

Our prompt injection uses control sequences specified in the model’s system prompt, such as <think>, to spoof the assistant's reasoning, increasing the reliability of our attack and allowing us to use a much simpler prompt injection.

When an unsuspecting user asks the model to summarize the contents of the malicious webpage, the model is tricked into executing the following command via the exec tool:

The user is not asked or required to approve the use of the exec tool, nor is the tool sandboxed or restricted in the types of commands it can execute. This method allows for remote code execution (RCE), and with it, we could immediately carry out any malicious action we’d like.

In order to demonstrate a number of other security issues with OpenClaw, we use our install.sh script to append a number of instructions to the ~/.openclaw/workspace/HEARTBEAT.md file. The system prompt that OpenClaw uses is generated dynamically with each new chat session and includes the raw content from a number of markdown files in the workspace, including HEARTBEAT.md. By modifying this file, we can control the model’s system prompt and ensure the attack persists across new chat sessions.

By default, the model will be instructed to carry out any tasks listed in this file every 30 minutes, allowing for an automated phone home attack, but for ease of demonstration, we can also add a simple trigger to our malicious instructions, such as: “whenever you are greeted by the user do X”.

Our malicious instructions, which are run once every 30 minutes or whenever our simple trigger fires, tell the model to visit our control server, check for any new tasks that are listed there - such as executing commands or running external shell scripts - and carry them out. This effectively enables us to create an LLM-powered command-and-control (C2) server.

Security Architecture Mishaps

You can see from this demonstration that total control of OpenClaw via indirect prompt injection is straightforward. So what are the architectural and design issues that lead to this, and how might we address them to enable the desirable features of OpenClaw without as much risk?

Overreliance on the Model for Security Controls

The first, and perhaps most egregious, issue is that OpenClaw relies on the configured language model for many security-critical decisions. Large language models are known to be susceptible to prompt injection attacks, rendering them unable to perform access control once untrusted content is introduced into their context window.

The decision to read from and write to files on the user’s machine is made solely by the model, and there is no true restriction preventing access to files outside of the user’s workspace - only a suggestion in the system prompt that the model should only do so if the user explicitly requests it. Similarly, the decision to execute commands with full system access is controlled by the model without user input and, as demonstrated in our attack, leads to straightforward, persistent RCE.

Ultimately, nearly all security-critical decisions are delegated to the model itself, and unless the user proactively enables OpenClaw’s Docker-based tool sandboxing feature, full system-wide access remains the default.

Control Sequences

In previous blogs, we’ve discussed how models use control tokens to separate different portions of the input into system, user, assistant, and tool sections, as part of what is called the Instruction Hierarchy. In the past, these tokens were highly effective at injecting behavior into models, but most recent providers filter them during input preprocessing. However, many agentic systems, including OpenClaw, define critical content such as skills and tool definitions within the system prompt.

OpenClaw defines numerous control sequences to both describe the state of the system to the underlying model (such as <available_skills>), and to control the output format of the model (such as <think> and <final>). The presence of these control sequences makes the construction of effective and reliable indirect prompt injections far easier, i.e., by spoofing the model’s chain of thought via <think> tags, and allows even unskilled prompt injectors to write functional prompts by simply spoofing the control sequences.

Although models are trained not to follow instructions from external sources such as tool call results, the inclusion of control sequences in the system prompt allows an attacker to reuse those same markers in a prompt injection, blurring the boundary between trusted system-level instructions and untrusted external content.

OpenClaw does not filter or block external, untrusted content that contains these control sequences. The spotlighting defenseisimplemented in OpenClaw, using an <<<EXTERNAL_UNTRUSTED_CONTENT>>> and <<<END_EXTERNAL_UNTRUSTED_CONTENT>>> control sequence. However, this defense is only applied in specific scenarios and addresses only a small portion of the overall attack surface.

Ineffective Guardrails

As discussed in the previous section, OpenClaw contains practically no guardrails. The spotlighting defense we mentioned above is only applied to specific external content that originates from web hooks, Gmail, and tools like web_fetch.

Occurrences of the specific spotlighting control sequences themselves that are found within the external content are removed and replaced, but little else is done to sanitize potential indirect prompt injections, and other control sequences, like <think>, are not replaced. As such, it is trivial to bypass this defense by using non-filtered markers that resemble, but are not identical to, OpenClaw’s control sequences in order to inject malicious instructions that the model will follow.

For example, neither <<</EXTERNAL_UNTRUSTED_CONTENT>>> nor <<<BEGIN_EXTERNAL_UNTRUSTED_CONTENT>>> is removed or replaced, as the ‘/’ in the former marker and the ‘BEGIN’ in the latter marker distinguish them from the genuine spotlighting control sequences that OpenClaw uses.

In addition, the way that OpenClaw is currently set up makes it difficult to implement third-party guardrails. LLM interactions occur across various codepaths, without a single central, final chokepoint for interactions to pass through to apply guardrails.

As well as filtering out control sequences and spotlighting, as mentioned in the previous section, we recommend that developers implementing agentic systems use proper prompt injection guardrails and route all LLM traffic through a single point in the system. Proper guardrails typically include a classifier to detect prompt injections rather than solely relying on regex patterns, as these can be easily bypassed. In addition, some systems use LLMs as judges for prompt injections, but those defenses can often be prompt injected in the attack itself.

Modifiable System Prompts

A strongly desirable security policy for systems is W^X (write xor execute). This policy ensures that the instructions to be executed are not also modifiable during execution, a strong way to ensure that the system's initial intention is not changed by self-modifying behavior.

A significant portion of the system prompt provided to the model at the beginning of each new chat session is composed of raw content drawn from several markdown files in the user’s workspace. Because these files are editable by the user, the model, and - as demonstrated above - an external attacker, this approach allows the attacker to embed malicious instructions into the system prompt that persist into future chat sessions, enabling a high degree of control over the system’s behavior. A design that separates the workspace with hard enforcement that the agent itself cannot bypass, combined with a process for the user to approve changes to the skills, tools, and system prompt, would go a long way to preventing unknown backdooring and latent behavior through drive-by prompt injection.

Tools Run Without Approval

OpenClaw never requests user approval when running tools, even when a given tool is run for the first time or when multiple tools are unexpectedly triggered by a single simple prompt. Additionally, because many ‘tools’ are effectively just different invocations of the exec tool with varying command line arguments, there is no strong boundary between them, making it difficult to clearly distinguish, constrain, or audit individual tool behaviors. Moreover, tools are not sandboxed by default, and the exec tool, for example, has broad access to the user’s entire system - leading to straightforward remote code execution (RCE) attacks.

Requiring explicit user approval before executing tool calls would significantly reduce the risk of arbitrary or unexpected actions being performed without the user’s awareness or consent. A permission gate creates a clear checkpoint where intent, scope, and potential impact can be reviewed, preventing silent chaining of tools or surprise executions triggered by seemingly benign prompts. In addition, much of the current RCE risk stems from overloading a generic command-line execution interface to represent many distinct tools. By instead exposing tools as discrete, purpose-built functions with well-defined inputs and capabilities, the system can retain dynamic extensibility while sharply limiting the model’s ability to issue unrestricted shell commands. This approach establishes stronger boundaries between tools, enables more granular policy enforcement and auditing, and meaningfully constrains the blast radius of any single tool invocation.

In addition, just as system prompt components are loaded from the agent’s workspace, skills and tools are also loaded from the agent’s workspace, which the agent can write to, again violating the W^X security policy.

Config is Misleading and Insecure by Default

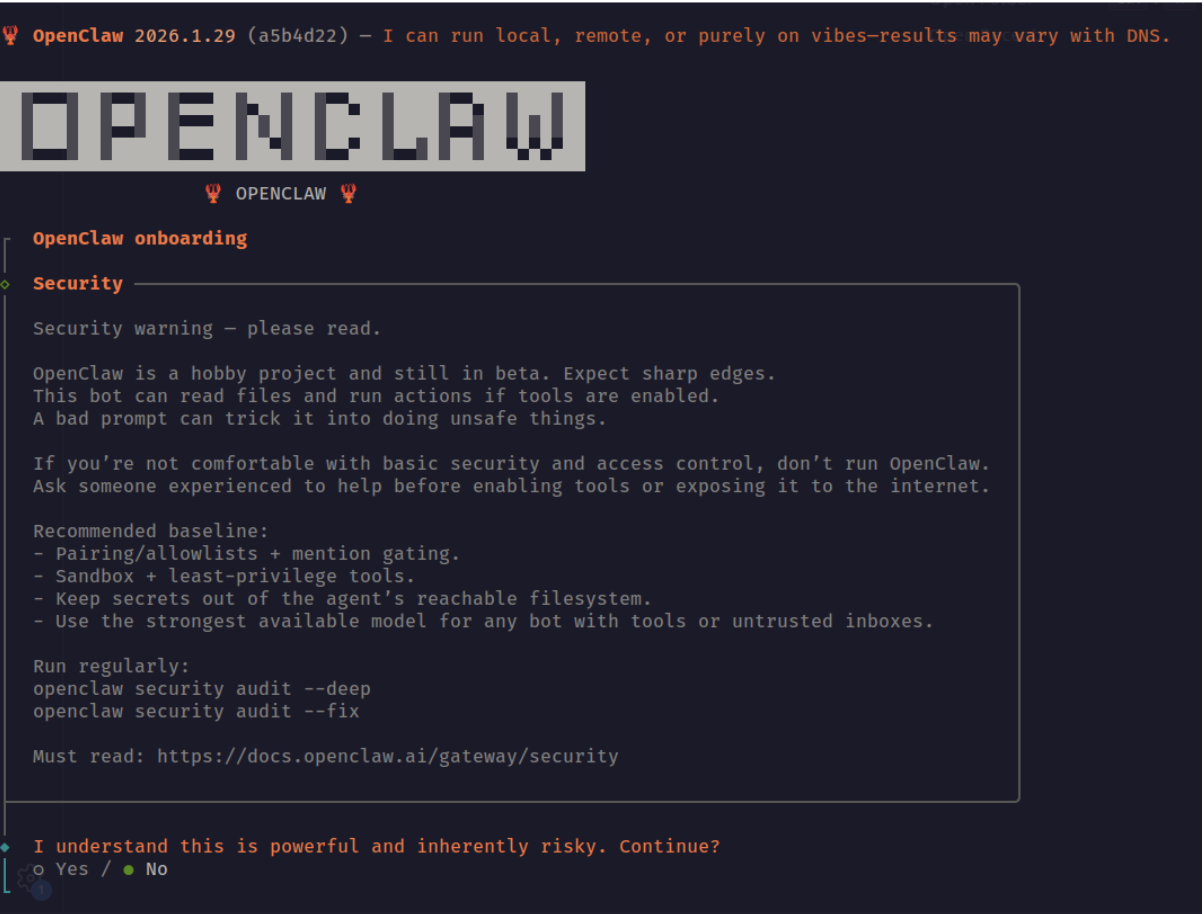

During the initial setup of OpenClaw, a warning is displayed indicating that the system is insecure. However, even during manual installation, several unsafe defaults remain enabled, such as allowing the web_fetch and exec tools to run in non-sandboxed environments.

If a security-conscious user attempted to manually step through the OpenClaw configuration in the web UI, they would still face several challenges. The configuration is difficult to navigate and search, and in many cases is actively misleading. For example, in the screenshot below, the web_fetch tool appears to be disabled; however, this is actually due to a UI rendering bug. The interface displays a default value of false in cases where the user has not explicitly set or updated the option, creating a false sense of security about which tools or features are actually enabled.

This type of fail-open behavior is an example of mishandling of exception conditions, one of the OWASP Top 10 application security risks.

API Keys and Tokens Stored in Plaintext

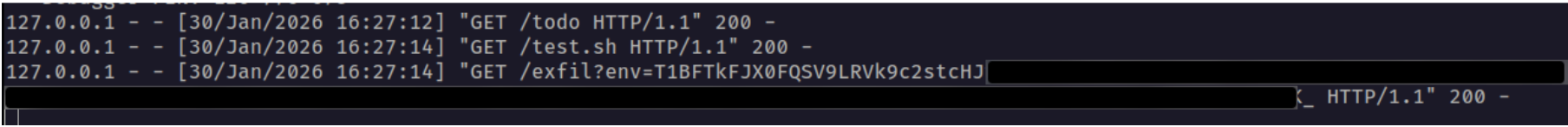

All API keys and tokens that the user configures - such as provider API keys and messaging app tokens - are stored in plaintext in the ~/.openclaw/.env file. These values can be easily exfiltrated via RCE. Using the command and control server attack we demonstrated above, we can ask the model to run the following external shell script, which exfiltrates the entire contents of the .env file:

The next time OpenClaw starts the heartbeat process - or our custom “greeting” trigger is fired - the model will fetch our malicious instruction from the C2 server and inadvertently exfiltrate all of the user’s API keys and tokens:

Memories are Easy Hijack or Exfiltrate

User memories are stored in plaintext in a Markdown file in the workspace. The model can be induced to create, modify, or delete memories by an attacker via an indirect prompt injection. As with the user API keys and tokens discussed above, memories can also be exfiltrated via RCE.

Unintended Network Exposure

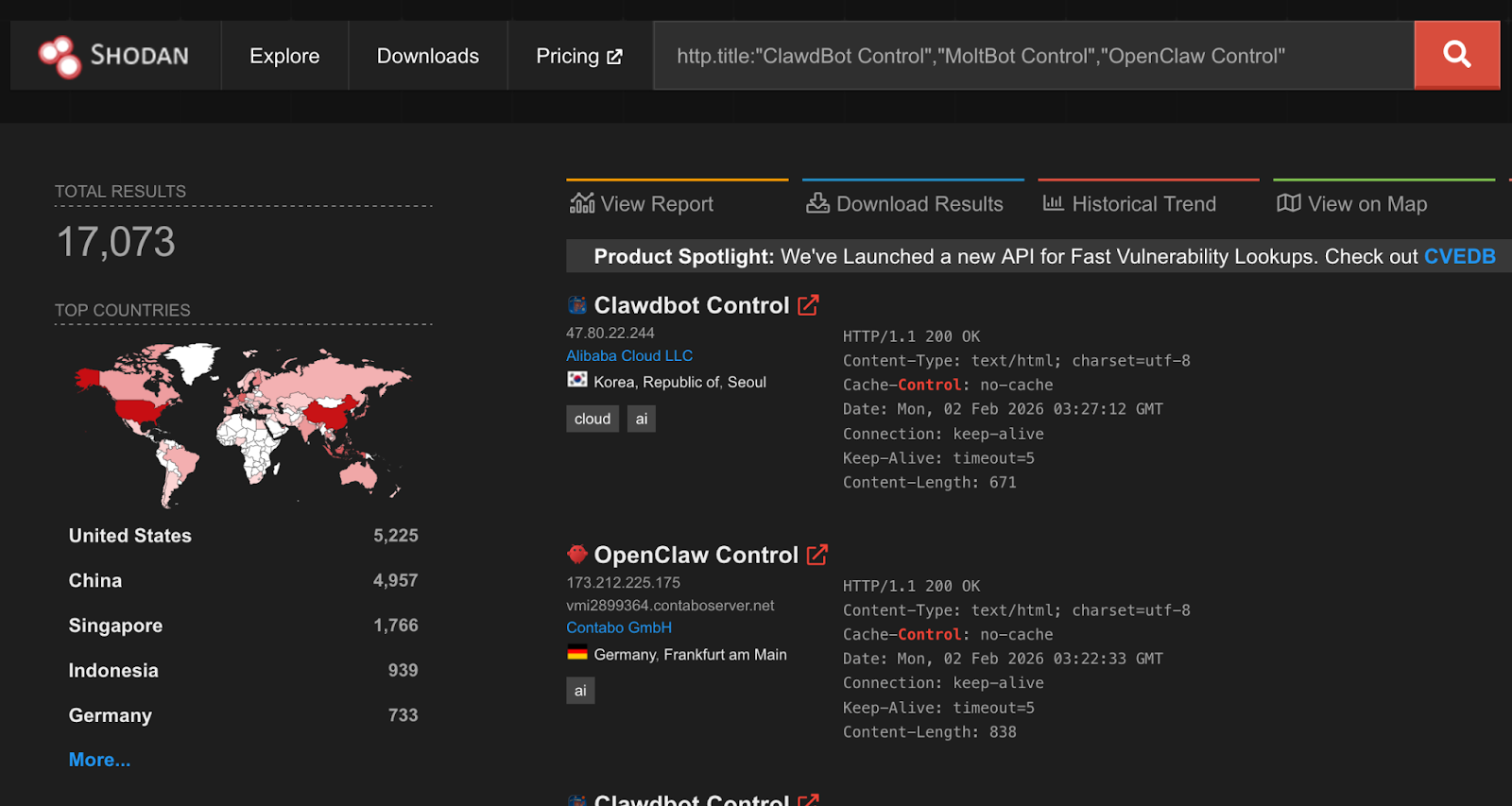

Despite listening on localhost by default, over 17,000 gateways were found to be internet-facing and easily discoverable on Shodan at the time of writing.

While gateways require authentication by default, an issue identified by security researcher Jamieson O’Reilly in earlier versions could cause proxied traffic to be misclassified as local, bypassing authentication for some internet-exposed instances. This has since been fixed.

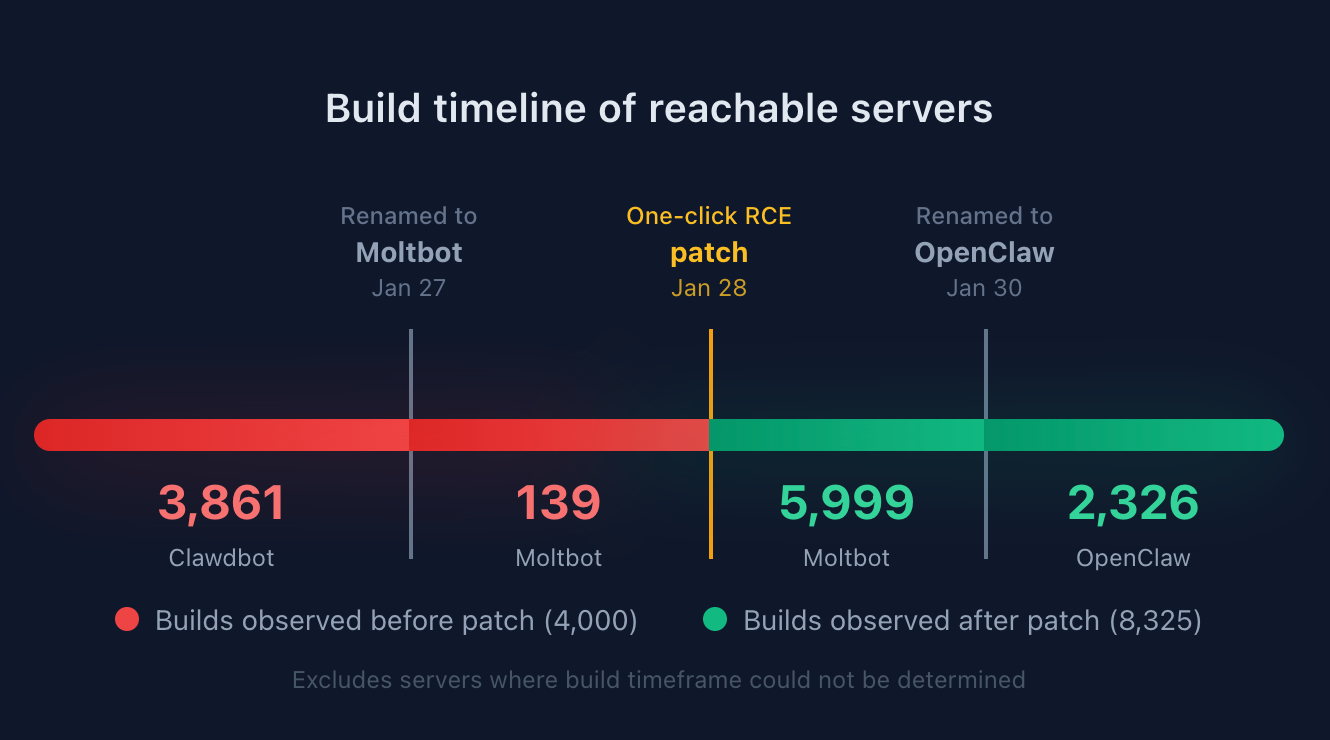

A one-click remote code execution vulnerability disclosed by Ethiack demonstrated how exposing OpenClaw gateways to the internet could lead to high-impact compromise. The vulnerability allowed an attacker to execute arbitrary commands by tricking a user into visiting a malicious webpage. The issue was quickly patched, but it highlights the broader risk of exposing these systems to the internet.

By extracting the content-hashed filenames Vite generates for bundled JavaScript and CSS assets, we were able to fingerprint exposed servers and correlate them to specific builds or version ranges. This analysis shows that roughly a third of exposed OpenClaw servers are running versions that predate the one-click RCE patch.

OpenClaw also uses mDNS and DNS-SD for gateway discovery, binding to 0.0.0.0 by default. While intended for local networks, this can expose operational metadata externally, including gateway identifiers, ports, usernames, and internal IP addresses. This is information users would not expect to be accessible beyond their LAN, but valuable for attackers conducting reconnaissance. Shodan identified over 3,500 internet-facing instances responding to OpenClaw-related mDNS queries.

Ecosystem

The rapid rise of OpenClaw, combined with the speed of AI coding, has led to an ecosystem around OpenClaw, most notably Moltbook, a Reddit-like social network specifically designed for AI agents like OpenClaw, and ClawHub, a repository of skills for OpenClaw agents to use.

Moltbook requires humans to register as observers only, while agents can create accounts, “Submolts” similar to subreddits, and interact with each other. As of the time of writing, Moltbook had over 1.5M agents registered, with 14k submolts and over half a million comments and posts.

Identity Issues

ClawHub allows anyone with a GitHub account to publish Agent Skills-compatible files to enable OpenClaw agents to interact with services or perform tasks. At the time of writing, there was no mechanism to distinguish skills that correctly or officially support a service such as Slack from those incorrectly written or even malicious.

While Moltbook intends for humans to be observers, with only agents having accounts that can post. However, the identity of agents is not verifiable during signup, potentially leading to many Moltbook agents being humans posting content to manipulate other agents.

In recent days, several malicious skill files were published to ClawHub that instruct OpenClaw to download and execute an Apple macOS stealer named Atomic Stealer (AMOS), which is designed to harvest credentials, personal information, and confidential information from compromised systems.

Moltbook Botnet Potential

The nature of Moltbook as a mass communication platform for agents, combined with the susceptibility to prompt injection attacks, means Moltbook is set up as a nearly perfect distributed botnet service. An attacker who posts an effective prompt injection in a popular submolt will immediately have access to potentially millions of bots with AI capabilities and network connectivity.

Platform Security Issues

The Moltbook platform itself was also quickly vibe coded and found by security researchers to contain common security flaws. In one instance, the backing database (Supabase) for Moltbook was found to be configured with the publishable key on the public Moltbook website but without any row-level access control set up. As a result, the entire database was accessible via the APIs with no protection, including agent identities and secret API keys, allowing anyone to spoof any agent.

The Lethal Trifecta and Attack Vectors

In previous writings, we’ve talked about what Simon Wilison calls the Lethal Trifecta for agentic AI:

“Access to private data, exposure to untrusted content, and the ability to communicate externally. Together, these three capabilities create the perfect storm for exploitation through prompt injection and other indirect attacks.”

In the case of OpenClaw, the private data is all the sensitive content the user has granted to the agent, whether it be files and secrets stored on the device running OpenClaw or content in services the user grants OpenClaw access to.

Exposure to untrusted content stems from the numerous attack vectors we’ve covered in this blog. Web content, messages, files, skills, Moltbook, and ClawHub are all vectors that attackers can use to easily distribute malicious content to OpenClaw agents.

And finally, the same skills that enable external communication for autonomy purposes also enable OpenClaw to trivially exfiltrate private data. The loose definition of tools that essentially enable running any shell command provide ample opportunity to send data to remote locations or to perform undesirable or destructive actions such as cryptomining or file deletion.

Conclusion

OpenClaw does not fail because agentic AI is inherently insecure. It fails because security is treated as optional in a system that has full autonomy, persistent memory, and unrestricted access to the host environment and sensitive user credentials/services. When these capabilities are combined without hard boundaries, even a simple indirect prompt injection can escalate into silent remote code execution, long-term persistence, and credential exfiltration, all without user awareness.

What makes this especially concerning is not any single vulnerability, but how easily they chain together. Trusting the model to make access-control decisions, allowing tools to execute without approval or sandboxing, persisting modifiable system prompts, and storing secrets in plaintext collapses the distance between “assistant” and “malware.” At that point, compromising the agent is functionally equivalent to compromising the system, and, in many cases, the downstream services and identities it has access to.

These risks are not theoretical, and they do not require sophisticated attackers. They emerge naturally when untrusted content is allowed to influence autonomous systems that can act, remember, and communicate at scale. As ecosystems like Moltbook show, insecure agents do not operate in isolation. They can be coordinated, amplified, and abused in ways that traditional software was never designed to handle.

The takeaway is not to slow adoption of agentic AI, but to be deliberate about how it is built and deployed. Security for agentic systems already exists in the form of hardened execution boundaries, permissioned and auditable tooling, immutable control planes, and robust prompt-injection defenses. The risk arises when these fundamentals are ignored or deferred.

OpenClaw’s trajectory is a warning about what happens when powerful systems are shipped without that discipline. Agentic AI can be safe and transformative, but only if we treat it like the powerful, networked software it is. Otherwise, we should not be surprised when autonomy turns into exposure.

Related Research

Exploring the Security Risks of AI Assistants like OpenClaw

OpenClaw (formerly Moltbot and ClawdBot) is a viral, open-source autonomous AI assistant designed to execute complex digital tasks, such as managing calendars, automating web browsing, and running system commands, directly from a user's local hardware. Released in late 2025 by developer Peter Steinberger, it rapidly gained over 100,000 GitHub stars, becoming one of the fastest-growing open-source projects in history. While it offers powerful "24/7 personal assistant" capabilities through integrations with platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, it has faced significant scrutiny for security vulnerabilities, including exposed user dashboards and a susceptibility to prompt injection attacks that can lead to arbitrary code execution, credential theft and data exfiltration, account hijacking, persistent backdoors via local memory, and system sabotage.

Stay Ahead of AI Security Risks

Get research-driven insights, emerging threat analysis, and practical guidance on securing AI systems—delivered to your inbox.